Open Letter from HateAid gGmbH and Counter Extremism Project to the governments of Sweden, Ireland and Finland

Are you safeguarding freedom of speech online or protecting the Big Tech?

To:

Mrs Heather Humphreys TD, Minister of Justice of Ireland

Mrs Anna-Maja Henriksson, Minister of Justice of Finland

Mr Morgan Johansson, Minister of Justice and Migration of Sweden

Dear Ministers,

The non-paper on Digital Services Act published by Sweden, Ireland and Finland on 18th of June poses a serious threat to all users, leaving them unprotected from the online violence. It proposes the obligation of platforms to assess and act within their content moderation to be limited to content that is manifestly illegal (instead of merely “illegal”). All other decisions shall be reserved for the courts. By doing so, your governments claim to safeguard freedom of expression, reduce over-removal, and minimize the administrative work for platforms. However, it is not that simple, carrying enormous implications for victims of digital violence.

From HateAid’s experience as a consultation centre that has already consulted more than 1000 victims of digital violence (that mainly took place on online platforms) in Germany, we consider this approach to be dangerous.

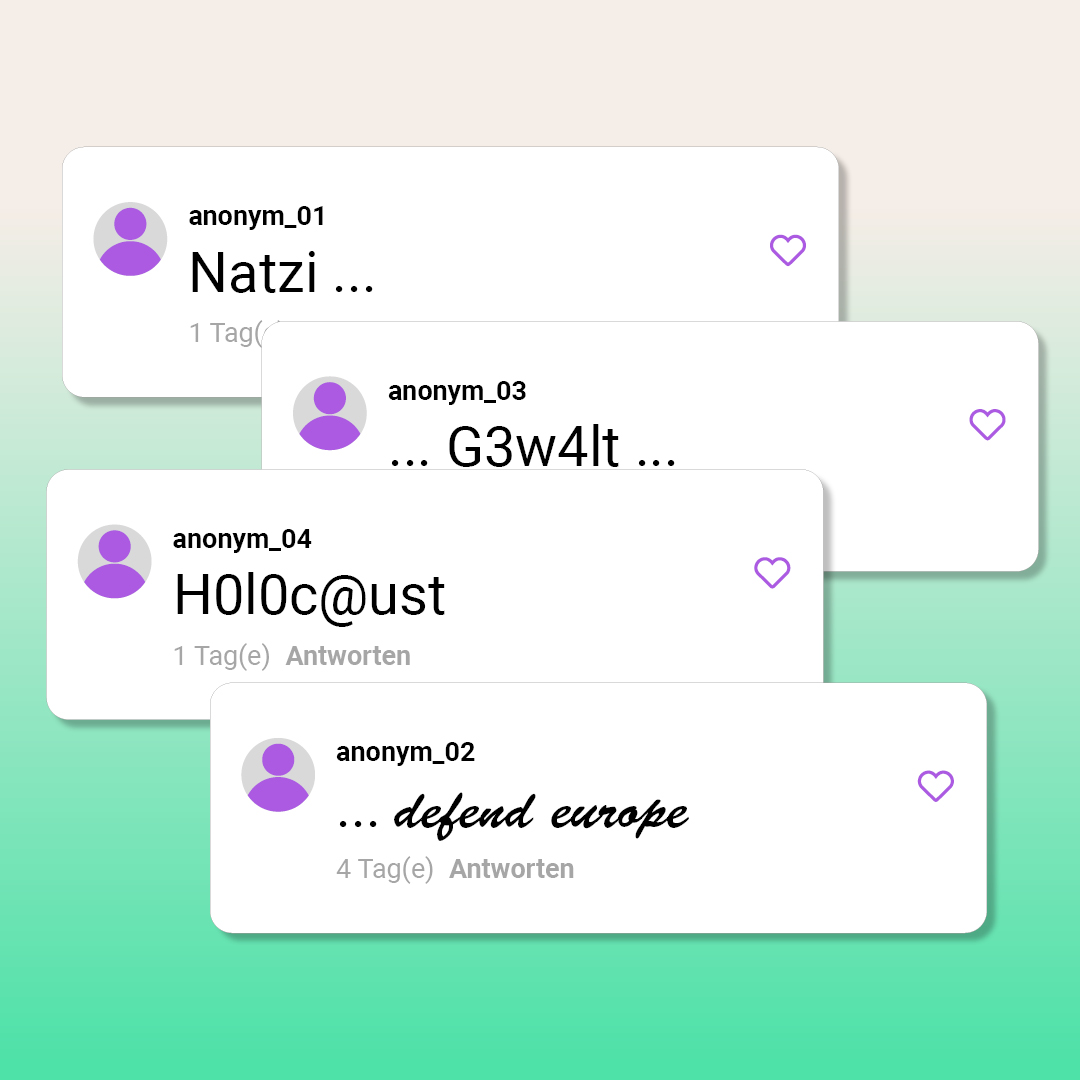

More people are withdrawing from public discourse online out of fear for their personal safety – because they have hardly any means of defending themselves against hate. While in the ongoing content moderation debate in Europe many tend to demonise take-down obligations and large, the users feel unprotected from the attacks that they are left to endure every day. The illegal content that they encounter is insulting, defaming, threatening and sometimes even putting their lives and the lives of their loved ones in danger, especially when their personal data is exposed. This is destabilizing our democracies and a threat to our European societies and the social cohesion on our continent. Large platforms profit from hate, but those affected suffer daily. We therefore urge you to reconsider your stance and instead of protecting the big platforms, stand up for the citizens.

Hate spreads all over the internet with the speed of light – to closed groups, private profiles, other platforms, and is flushed into various timelines and the public by intransparent algorithms. The victims can never be sure of the information being fully removed and frankly can only pray that it does not reappear somewhere eventually again. For victims it is irrelevant if the content in question is “manifestly” illegal or only “ordinarily” illegal. Due to a lack of protection and access to justice they only see one choice: withdrawal and silencing, resulting in the loss of their voices in what was supposed to be open and public debate. Even more, women, people of colour, ethnic minorities, LGBTQI+ community and other groups are the ones affected the most. In our opinion, this is a threat to freedom of expression that must be taken equally serious and can only be solved by making the internet safer for everybody. The fact that the online platforms are strategically instrumentalized to silence marginalised groups by harassing them should cause an outcry.

54 % of the internet users in Germany do not longer dare to express their political opinion online and 47 % rarely participate in online discussions at all out of fear of becoming victims themselves.1 This silencing effect is not only a German phenomenon, but equally relevant in your countries. A Finnish study from 2019 found that 28 % of municipal officials targeted with hate speech said they were less willing to participate in decision-making as a result.2 The Archbishop of Sweden, Antje Jackelén, “took a break” from Twitter after she experienced hate attacks,3 while Mike Cubbard, mayor of Galway (Ireland), took a 2 weeklong break from his mayoral duties after receiving threats through online comments.4 These examples are just a few of many cases where women, local politicians, and many others are overwhelmed by the hate they encounter online, which makes them feel unsafe and become silenced with many bystanders following their example.

The non-paper also disregards the fact that the liability for online platforms is very theoretical as this requires users to take legal action to claim the liability. This is rarely happening as we have serious issues with access to justice in this regard: legal proceedings take too long, and the financial risk often exceeds a month’s salary. Therefore, the victims cannot be expected to claim the liability and the platforms are not only aware of this, but they count on it. HateAid argues that it is Member States‘ and the European Parliaments‘ role to agree on fast-track court proceedings for content decisions in every Member State.

Instead of having user’s interests at heart, the three governments are concerned with putting the administrative burden on the platforms. We need to acknowledge that it is social media platforms that have enabled online hate through algorithms and business models that favour sensational content and do not have adequate protections put in place. Those US- American for-profit companies have accidentally slipped into a gatekeeper role for digital public debates in the EU – a role they were not designed for and which, because of their business model of maximizing, manipulating and monetizing all available data of their users, creates toxic effects for EU societies and individuals. Therefore, every solution to tackle the hate speech crisis needs to take in account the role of the social media platforms. Now we need to find a way to deal with the harmful consequences that this business model has created not only for the citizens of the EU but also for society as whole. Platforms need to take responsibility to protect users and contain the negative effects of their business model. The EU governments do not have a lesser role to play – with Facebook and other platforms asking the regulators to do their job and introduce rules for years.

What users now need is an enforceable obligation to delete illegal content, at the same time introducing balanced redress mechanisms for all users to appeal potentially wrongful content decisions. The courts should be available under reasonable conditions as the final instance to deem the content legal or illegal.

We call on you to rethink the position outlined in the non-paper and to take the side of users, considering the silencing effect, severe effects of online violence on the users but also our democracies, and the platforms responsibility to solve the hate speech crisis.

Sources

1 D. Geschke, A.Klaßen, M.Quent, C. Richter, 2019. #Hass im Netz: Der schleichende Angriff auf unsere Demokratie. Eine bundesweite repräsentative Untersuchung. Institut für Demokratie und Zivilgesellschaft, Germany. ISBN: 978-3-940878-41-0

2 L.Cater, Politico, 2021. Finland’s women-led government targeted by online harassment. https://www.politico.eu/article/sanna-marin-finland-online-harassment-women-government-targeted/. Viewed 29/06/21

3 Antje Jackelén, @BiskopAntje, 5.04.2021. Tar twitterpaus. Berörs illa av att mina tweets används för att sprida hot och hat samt lögn om tro, @svenskakyrkan & samhället. Ni som gör det kan känna er som vinnare för stunden. Men: den sanna vinnarsidan är alltid sanningens och kärlekens sida. Växla över till den!, [Tweet] Twitter, https://twitter.com/BiskopAntje/status/1379044967193120772

4 S.Pollak, 2021, Irish Times. Mayor of Galway city to return to duties after break following abuse. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/politics/mayor-of-galway-city-to-return-to-duties-after-break-following-abuse-1.4523297, Viewed: 29/06/21

5 Policy Brief “notice and (NO) action”: Lessons (not) learned from testing the content moderation systems of very large social media platforms. Counter Extremism Project, June 2021.

https://www.counterextremism.com/sites/default/files/2021-06/CEP%20Policy%20Brief%20on%20DSA%20NoticeNOAction%20June%202021.pdf

6 European Commission, 2018. Flash Eurobarometer 469: Illegal content online, https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2201