Digital Services Act: HateAid demands #PowerToTheUsers

Why help shape the EU’s new platform law?

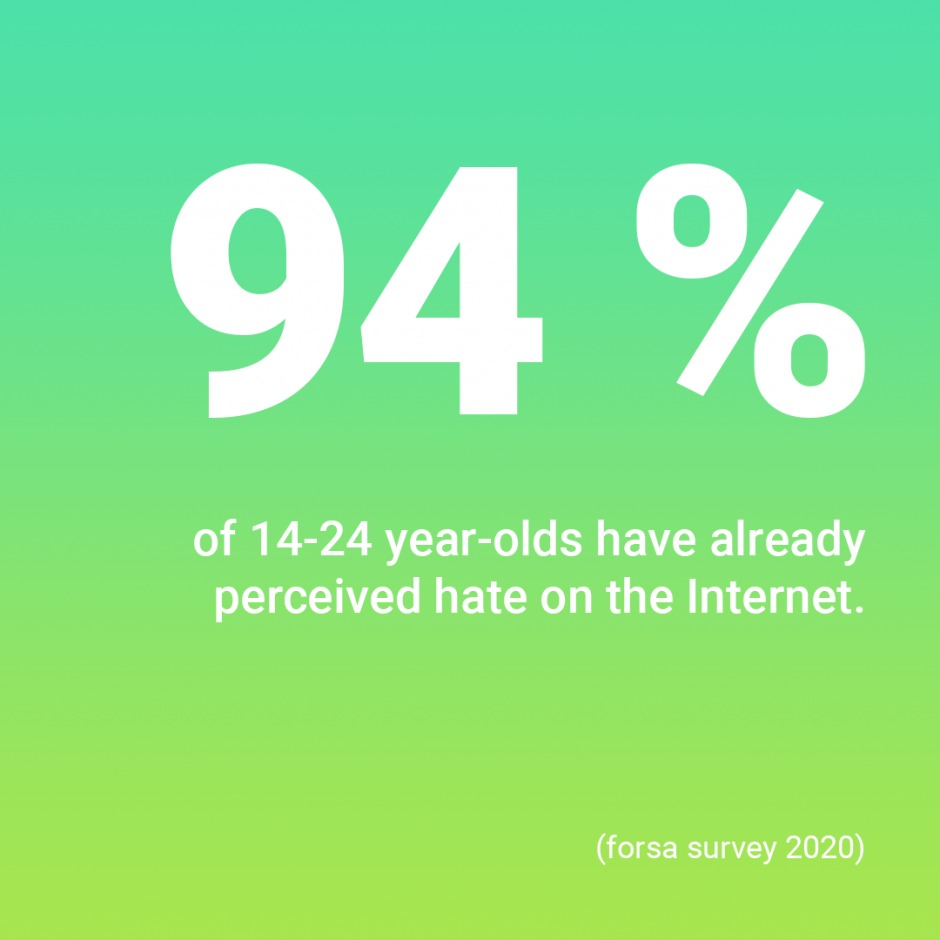

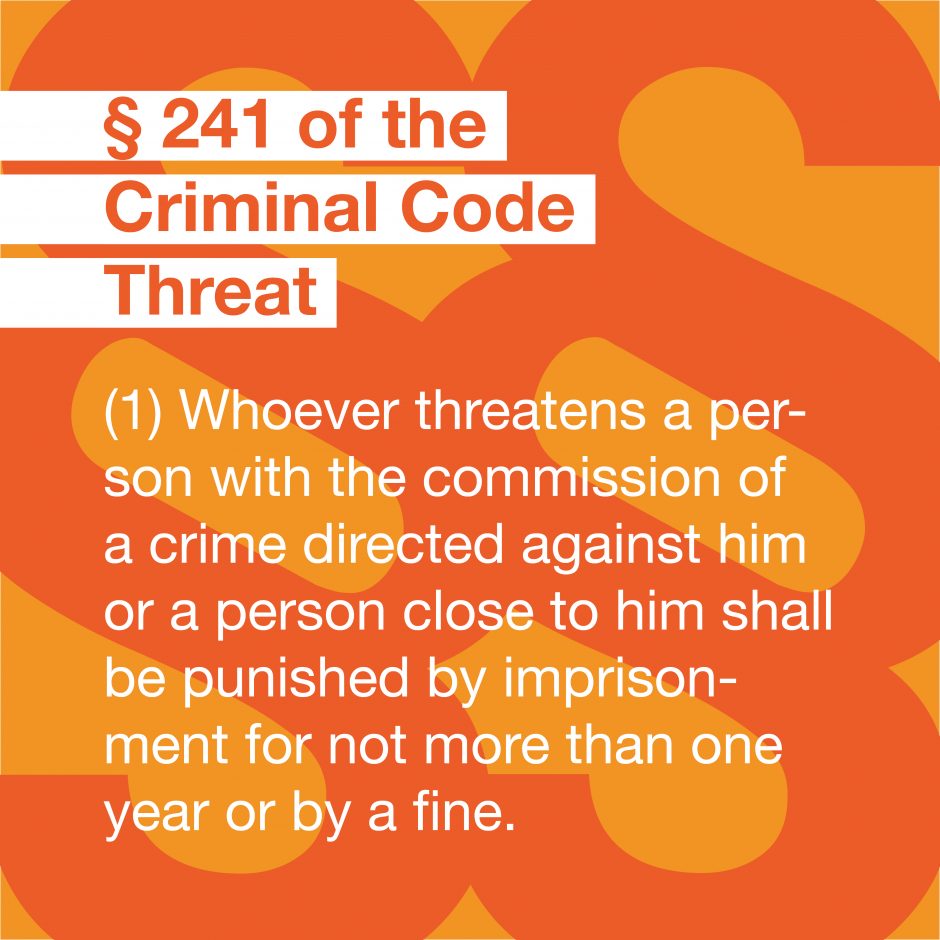

Imagine: Someone takes your picture from the net, makes a meme out of it with the quote “The government should lock up the Corona cross thinkers. My opinion.” This meme is then spread via various (fake) accounts – on Facebook, Twitter – and quickly also in unpleasant rounds on Telegram. This is followed by various reactions on your profile, including those that can quickly scare you – such as death threats or even the publication of your address. For women, it gets particularly intense when they have to endure rape fantasies, for example. Cases like these are the subject of the Digital Services Act (DSA), which will be negotiated in more concrete terms from June 2021.

Hate can hit anyone, and it hits many people completely unexpectedly. What can you do? If you want to report hate messages, violent comments or defamation of character, the problem is just beginning: You mark perpetrator profiles and report postings. And then…. you don’t hear from Facebook, Instagram, Twitter or TikTok. The meme remains, your helplessness, shame and fear of the aggressive unknown perpetrators gets worse every day.

Digital Violence has many faces – we support those affected all the way to the highest courts

More security in the German network – and in the EU: that’s what we want to achieve:

- Security and Support: For example, through simple and understandable access to platform support, fast reporting options, checking and deletion of illegal content. User support centers are available 24/7 in case of emergency.

- Clear rights: If the platform support is unable to help you, it must be clear how you can enforce your rights in Germany. Instead of looking for an address abroad, learning another language or going straight to law school, you know exactly who you can turn to and how you can find help.

- Transparency: All users of platforms such as Google, Facebook, TikTok, Twitter and other services should be able to see easily and clearly what their rights, options and limits of use are. Decisions of the platforms should be justified so that they are comprehensible.

- Responsibility: There must be clarity about which country’s law applies if something happens to you on the Internet and how you will be helped in Germany – as well as in all other EU countries.

What YOU can do

If you want to help fight hate, violence, and lack of transparency online, join our campaign for a Digital Services Act that best serves the interests of a democratic society and a hate-free web – and better protects you online.

All in-depth information on the Digital Services Act in Germany and Europe

What is the Digital Services Act and how does it work?

The Digital Services Act is a draft regulation of the European Commission that was presented on December 15, 2020 – so far only in English. The full title is: “Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on a Single Market For Digital Services (Digital Services Act) and amending Directive 2000/31/EC”.

What is new in the DSA?

According to the European Commission’s website, the new Digital Services Act is intended to offer more security and responsibility in the online environment. It goes on to say: “For the first time, a single set of rules on the obligations and responsibilities of intermediaries opens up new opportunities to offer digital services across borders throughout the single market – with a high level of protection for all users, regardless of where they live in the EU.

The focus of the Digital Services Act in Germany and the EU

The Digital Services Act initially applies to intermediary services such as ISPs and domain name registrars, hosting services such as cloud and web hosting services, and online platforms such as online marketplaces, app stores, and social media platforms.

Why is HateAid working on that topic and does all of this mean there will be a lot of Overblocking?

The focus of HateAid is primarily on social networks and the rights of users vis-à-vis them. We are committed to ensuring that users are no longer powerless in the face of the overpowering networks, especially when it comes to content moderation. This requires clearly regulated and easily accessible processes for dealing with illegal content and transparent decision-making processes that are open to scrutiny. Until now, the opposite has been the case: users can hardly understand deletion decisions and especially “non-deletion decisions”; they often appear arbitrary. Those affected are fobbed off with terse text modules and have hardly any legal means of challenging such decisions.

From HateAid’s point of view, the strong focus on measures against abusive reporting and possibly unauthorized deletion of content in social media is problematic in the draft of the Digital Services Act: According to the will of the European Commission, the corresponding regulations are intended to prevent a restriction of users’ freedom of expression. Such a restriction could arise from the fact that certain postings are systematically reported by other users and then deleted without there actually being a reason for deletion (so-called overblocking). In contrast, however, the draft takes too little account of the call for consequences for social media providers in the event of underblocking, i.e. if legitimate interests of users in the deletion of certain posts are ignored.

Who does the Digital Services Act apply to?

Additional requirements under the Digital Services Act apply to very large online platforms that reach more than 10% of the 450 million consumers in Europe. As platforms of this size pose particular risks for the dissemination of illegal content and for damage to society, they are subject to further strict rules, such as risk management obligations and the appointment of compliance officers, external risk audits and public accountability, transparency of recommendation systems and choice for users when accessing information (to counteract the “opinion bubble”), data exchange and cooperation with authorities and research institutes).

So-called “Digital Services Coordinators” are responsible for each country. At present, the question remains open as to how individual EU states, in which a particularly large number of tech companies are headquartered, can meet their new and expanded responsibilities. For example, Google and Facebook, among others, have their official European headquarters in the Republic of Ireland. This places a particularly large responsibility on the Irish “Digital Services Coordinator” and the Irish courts could also find themselves exposed to a large number of additional cases if companies violate the Digital Services Act.

In Germany, the Network Enforcement Act (NetzDG) is a set of rules that addresses many of the challenges posed by social media.

The new law will mean far-reaching changes in society, similar to the GDPR

The reach of the Digital Services Act can be glimpsed in the resounding impact of the German Data Protection Regulation (DSGVO / General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)), which since 2018 has raised EU-wide data protection requirements to a level similar to that which previously applied in Germany through the Federal Data Protection Act.